Campania: Art, Architecture and Coins Coins: Latin and Italian Allies

|

Links to Campania Art, Architecture and Coins; Coins: Latin and Italian Allies

- Discussion and Pictures of Coins: Latin and Italian Cities

- Book Reviews: Latin and Italian Coins

- Campania: Art Architecture and Coins, a phote-essay

- Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

- Paestum, a Greek, Samnite and Roman City

- Sculptures from the Villa of the Papyri - A Philosophers Home

- Vesuvian Villas, Boscoreale, Oplontis, Stabiae and Villa of Mysteries

- Puteoli, Cumae and the ageless Sibyl

- Pompeian Frescos at the Naples Archaeological Museum

Coins: Latin and Italian Cities

Click on any photo to see that coin. Or click on the right-hand blue link to see the entire set.

Latin and Italian Cities

Click for SLIDE SHOW of these coins

Click for DETAIL VIEW of these coins

www.flickr.com

![]()

Latin & Italian allies

A number of independant-minded Italian cities continued to issue coins after their conquest by Rome, using the Roman monetary standards. In almost all cases they were small change issues, indeed often the very smallest of small change. The first such coins were the quartunciae issued by Cales and Cosa with Roman - not Greek - letters. In the case of Cosa, Roman types were used, indeed I always have a close look at any Mars Horsehead Crawford 17 Quartuncia in the hope of finding a coin from Cosa. For much of the third century BC, Italian cities issued Aes Grave with their own types but Roman denominations. At one point during the second Punic war Luceria aes grave types were apparently issued alongside those of Rome to the same weight standard, both marked with the L for Luceria mintmark. A number of examples are in this set. It is not clear what was the purpose of issuing both local and imperial coinage from the same mint as the issues were large, much more than needed to satisfy civic pride. During and after the second Punic war the issues became more standardised with a number of Italian cities striking bronze. Brundisium post-semilibral bronzes were clearly part of the Roman post-semilibral monetary system, and the same types continued to a much later period. Luceria and Brundisium were exceptions in striking heavy bronzes. Most cities struck to sextantal and lighter weights suggesting second century BC dating. There was a pattern of just a few cities striking in large volume whilst many more struck attractive coins in small volumes perhaps for civic purposes. For example a semuncia from Venusia displays an elegant winged boot. Larinum is an unusual example in using its local Latin (not Roman) alphabet. All cities stopped issuing coins after the social war with the exception of the semisses of Paestum which continued until early Imperial coins with often proudly civic types such as one depicting its senate house. Also this set includes a couple of Etruscan coins apparently on the Roman standard. Etruscan post semilibral bronze designs remain wholly native. There has been much debate about the late Estruscan silver standard with speculation that the Gorgon/blank with XX denomination reflected two Roman denarii. There is divergent opinions on these coins and it is worth reading both the opinion of Andrew Burnett in HNI, and of Italo Vecchi in the Celator.

Books: Latin and Italian Coinages

Essential books on Italian Coinage

Any Republican numismatist who needs a basic understanding of coinage in the context of Rome's conquest of Italy and the Mediterranean needs both Historia Numorum Italy and Coinage and Money in the Roman Republic. HNI contains, in addition to Italy, quite some news on early Roman (pre-denarius) coinage. Crawford’s CMRR is the glue that binds it all together, Rome, Italy and the Provinces, in a grand sweep of numismatic history.

Historia Numorum - Italy, NK Rutter, British Museum 2001

Historia Numorum Italy - HNI, is separately reviewed in the Other Key References section.

Coinage and Money Under the Roman Republic: Italy and the Mediterranean Economy, Michael Crawford, 1985

Coinage & Money Under the Roman Republic - CMRR, is separately reviewed in the Other Key References section, and includes a perspective on the various non-Roman coinage in Italy.

Useful and Interesting books on Italian Coinage

The following books will be of greater or lesser interest dependant on the extent of your interest in the coins of Italy during the Roman Republic. Catalli's book is especially nice, and integrates Italian coinage well with that of Rome. The monograph on Paestum is a rare example of a focussed text on a single Italian city coinage. Of course the local imitative coins used in Italian cities must also be studied for a proper understanding. These are discussed on a separate page, dealing with Imitative Coins and Locally made Small Change

SNG France VI,1: Italie, Etrurie - Calabre. Bibliotheque Nationale Dept. des Monnaies, Médailles et Antiques 2003

Invaluable for its 141 pages of plates illustrating many coins not pictured in HNI.

Les Monnaeis Antiques de l’Italie, Sambon, Paris 1903.

An attractive older book covering the same scope as HNI, with many illustrations in text, a mix of line drawings and photos as well as some plates that include early Roman coinage as well as Social War coinage. French. Whilst superseded by HNI it is a nice volume to browse.

Monete dell’Italie Antica, Fiorenzo Catalli, Rome 1995

A companion volume to Catalii’s book on the Roman Republic but this time covering a very similar scope to HNI (which it pre-dates) or Sambon, including Aes Grave and later Italian bronzes. Of course most of the book covers coins of Magna Graecia, but about a third is relevant the Republican era and the discussion is valuable. It also discusses and proposes dating on all the Roman pre-denarius coins. Unlike its companion Republican volume it does not include a catalogue.

Paestum and Rome, the form and function of a subsidiary coinage, Michael Crawford, in La Monetazione di bronzo di Poseidonia - Paestum, 1973

Catalogue and discussion of Paestum bronzes. Crawford concluded that the later small bronzes struck through most of the Republic were donative issues struck by prominent citizens and benefactors and authorised by the senate at Paestum, not by Rome> He considers it was just by chance and local circumstances that only Paestum struck civic bronzes in the late Republic. Quote, Its function was almost entirely frivolous and it tells us nothing about the right of Paestum or of any other place under Roman rule to coin, Unquote. This may have a wider implication for many other small change issues of the Republic, some very finely produced to high standard such as the official unciae of the second century BC which probably also had donative or commemorative purposes and other more common local change issues produced to lesser or greater quality. However see, contrary, Clive Stannard in AJN20 above.

Campania: Art, Architecture and Coins

- Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

- Paestum, a Greek, Samnite and Roman City

- Sculptures from the Villa of the Papyri - A Philosophers Home

- Vesuvian Villas, Boscoreale, Oplontis, Stabiae and Villa of Mysteries

- Puteoli, Cumae and the ageless Sibyl

- Pompeian Frescos at the Naples Archaeological Museum

Windows into the real life of Ancient Rome are small, blurred and cracked. However grand the monuments, Rome doesn't gives up much. Arches, Colosseum, gladiator-dress photo-opportunities, scattered columns in the forum and some wonderful sculptures in the Capitoline doesn't amount to life itself. Literature is a different matter. We get a better view of life from Cicero's letters than from any number of chipped marble columns. In Campania, a lucky break for posterity has given us two fossilised cities, Herculaneum and Pompeii, and surrounding villas at Oplontis, Boscoreale, Stabiae and elsewhere, as well as some decent ruins at the north of the bay, Puteoli, Cumae and Baiae. The towns were small, ordinary and insignificant in the Roman world with middle-class houses amongst the wealthy and servile class. This story of Campania: Art, Architecture and Coins follows a recent visit to Naples. where I focussed on the domesticity of Herculaneum and the small villas, with their domestic wall-painting and architecture, rather than the grandeur of Pompeii, and compared the images with the government and imperial perspective on the Roman world given by our coins. I did find some surprises: Bacchus and Bread, Wine and Entertainment are rather more prominent than Mars and War. Perhaps this shouldn't be a surprise.

| www.flickr.com |

Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

Herculaneum is the destination of second choice for first time visitors to Naples. There is no large Forum, no Amphitheatre at least not as yet excavated, no Temples, few large houses and a much smaller scale. It is compact and domestic but on average much better preserved than Pompeii, with two storied houses having intact woodwork and other organic matter due to it being buried in mud rather than pumice showers. Save for the House of the Papyri, Herculaneum's preservation is also down to the luck of being second best. Many of the best frescoed dwellings in Pompeii had their wall coverings removed and brought to Naples where they are now in the Archaeological Museum. What's left in Herculaneum is just as atmospheric, decorative and helpful for understanding the lifestyle of a Roman city house, even if the greatest art is mainly Pompeian and in the museums. Still the city is not small. Several hours are needed to take in the three by three square of the excavated streets, at a pace slow enough to properly contemplate the lives of the ancients.

Click for Slide-Show of Herculaneum

Click on any picture below to enlarge

The House of Neptune and Amphitrite

has a garden room in place of the usual peristyle, richly decorated with mosaics. It's not a huge house,

which explains its non standard arrangements - there's no room for a peristyle - but the quality of the mosaics

and general decorative standard indicates a wealthy proprietor.

On one wall of the garden court are some recessed areas perhaps for statues or Lares, with

mosaics of dogs and stags

surrounding, and above them theatre masks. The garden court wall mosaics use pieces of glass to give the

vivid colours and reflect light, and thus are brighter and more colourful than more robust floor mosaics made of tile.

That of Neptune and Amphitrite his consort is oddly named. The Roman names should be Neptune and Salacia or Greek

Poseidon and Amphitrite, but it's very nautical in any event with brights sea shell surrounds and predominantly

sea blue, a colour that doesn't appear much on Vesuvaian walls.

There is a rare and elegantly engraved Roman coin with the same types usually named thus,

Neptune in a biga of hippocamps and Amphitrite with behind her a squid, minted by one Crepereius in 69BC. Fishy.

Lares were ghost-like beings, disembodied spirits of ancestors, who preserved the home and family.

Lara was a gossipy naiad who told Hera-Juno that Zeus-Jupiter loved Juturna. Jupiter told Mercury to take

Lara to Hades. Mercury seems to have tripped en-route as he begat with Lara the twin brothers, Lares, who

became protectors of home, cross-roads and cities.

Cremated remains were once buried inside houses and their spirits

protected the inhabitants. In time the Lares took the place of the actual remains.

Usually the statues were primitive and cast in bronze, wrapped in dog-skins,

and placed in a niche such as this in the House of the Black Salon, sometimes with small figures of barking dogs.

Even poorer Romans might own a couple of small crude bronze figures.

Lares were always associated with dogs, but the reasons were lost in time's mists.

Plutarch asked why is a dog placed beside the Lares, why are they clothed in the

skins of dogs, is it because those who stand before a house should be its guardians, terrifying to

strangers, but gentle and mild to those who live there, even as are dogs? Or is it that the Lares are

spirits of punishment like Furies and supervisors of men's lives and houses? The coin of Lucius Caesius

shows the twin Lares in the dog-skins with a barking dog.

The College of Augustales

in a town such as Herculaneum were appointed by the emperor Augustus. under advice from the

town councillors or Decurions, from amongst freedmen i.e. ex-slaves to

attend the rites of the Lares associated with the meeting of ways at that town, the municipal equivalent of the

household Lares. After the time of Augustus no doubt their focus switched to attending to the rites of the god

Augustus thus mirroring the activities of the Imperial priesthood of the Augustales at Rome. Decurions were

required to be free-born and thus barred to ex-slaves. Thus Augustales provided an honoured means by

which richer freedmen could attend to civic duties, with the associated expenses that always implied

whether for entertainments, support for the needy, or town infrastructure improvements. Herculaneum

was a small town of some thousands, perhaps its Augustales might have numbered a hundred or so and

constituted a middle-class cadre rather above the plebs despite not being free born. Their pictured college

building is quite splendidly decorated, and that decoration focusses on the myths of Hercules,

from whom the town was named, in the frescos to left and right. Hercules was a mortal demi-god, son of

Jupiter and Alcmene, the granddaughter of the legendary Perseus, founder of Mycaenae. Elsewhere on this webpage

I describe his tangles with centaur and wife Deianira that led to his ultimate death.

The very first silver coin struck at Rome in 269BC, as referred to by Pliny, has as its type

Hercules and the Wolf and Twins.

The coin shown above is the first struck-bronze bearing Hercules, around 230BC, with his club and Pegasus on

the reverse. Sadly in Greek mythology Hercules and Pegasus don't cross paths, but Disney fixed that in the

movie Hercules, where Pegasus is created by Zeus out of a cloud and keeps Hercules company at all times.

A comparison of plotlines shows

Disney pulled its punches,

stepping back from Deianira's nastiness and other such soft-soaping. Oddly, in the stakes for children's

education the original myths perhaps did a better job of moralising, showing the bad side of life and the

consequences of poor-decision making.

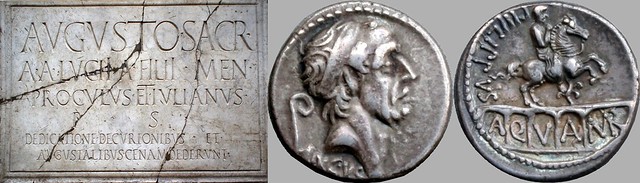

The commemorative tablet at the College of the Augustales is sharp and unworn. Romans didn't forget

but commemorated right left and centre and often with marble plaques. The coin of Marcius Phillipus is typical

with several commemorative elements. Ancus Marcius, Rome's fourth king, is shown on the obverse, whilst the reverse shows

the aquaduct Aqua Marcia with its arches, an equestrian statue of who knows whom, and AQVA MAR clearly written

on the aquaduct as if the words were on an inscribed tablet which doubtless they were. The Marcia

coin says don't forget that we gave you clean water. The Herculaneum tablet

dedicates the building to Augustus, on which day the brothers Proculus and Julian Lucius, no doubt ex-slaves

and Augustales, and from the same prior owner Lucius given their common family name,

gave a banquet to the Decurions - city councillors - and members of the Augustales.

This tablet says don't forget that Proculus and Julian gave you a free lunch.

Triton was the son of the Olympian Poseidon, or Roman Neptune, and the Oceanid (or Nereid) Amphitrite.

He was a merman with two fishtails for legs

and carried a horn. Triton appeared to the Argonauts, stranded in the Libyan desert and pulled their ship (Argo)

back to the sea. This superb mosaic is on the floor of the

Women's baths in Herculaneum

where Triton is

surrounded by other sea animals, squid, octopus and dolphins. It's amusing to think of a naked, muscular

merman as the main feature in the women's bath changing room, with red-painted benches around, and above their heads

cubicles for their clothes. I guess it attracted much the same comments as a naked mermaid would in a mens

changing room. Changing room etiquette seemed to be that a servant or slave, presumably a woman in this case but who

knows, would look after the clothes, possibly for a small tip. Various ancient sources, reflected in today's novels of

ancient Rome by authors such as Steven Saylor, suggest that baths were warm and busy places with petty theft,

exotic massage services and the like on offer. Bear in mind that none save the exceptionally rich had baths at home,

so poor and wealthy, young and old, all met together in their skins. No Roman Republican coin shows Triton

directly but coins of Sextus Pompeius, who was as close to a real merman as one could get, consistently have

watery scenes and this with Neptune and a trophy including naval elements - trident, ships prow and aplustre

or stern ornament - and with the hound-headed legs of the Scylla, is a special favourite.

This roofward view towards an upstairs Herculaneum balcony is something you won't find much of in Pompeii. Pompeii was

buried deep by raining hot ash and pumice stone, destroying upper level structures and burning woodwork in a way that

did not happen in Herculaneum which was engulfed in a pyroclastic surge of hot ashes, gas and water forming a

hot mud that flowed into the buildings. Though smaller and - apart from the Villa of the Papyri - less rich

in content, Herculaneum feels better preserved, with surving

charred ancient woodwork

and many houses with upper storey features. The

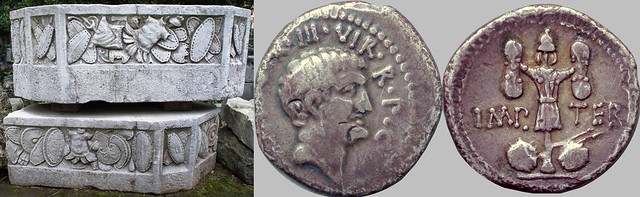

House of the Bronze Herm is so-called from the Herm or terminal bust of the owner in the atrium, inset in the

photograph. Statues in herm form were considered to ward off evil and often placed at crossings or boundaries.

Sometimes the pillar included sculpted genitals as their only decorative feature. Terminal busts or Herms appear

from time to time on Roman coinage, and so that we make no mistake, this terminal bust of Jupiter shows the square

end-pieces protuding prominently. Admiral Smyth in his catalogue of the Duke of Northumberland's collections

notes these terminal busts as being as innocent and protective as hedgerows. Interesting analogy.

The

House of the Black Salon in Herculaneum is impressive not just for the pictured Triclinium, which looks out

onto an elegant peristyle, but, given the close confines of Herculaneum, for the sheer amount of public space in the

residence. Looking from the

Peristyle through the Tablinum to the Atrium and entrance,

try imagine how it would have appeared with decorations and structure intact and

without the hoards of tourists, larger than it seems today. Without statues or much in the way of figurative

painting at the site, I struggled how to numismatically represent these houses of the wealthy,

but I think an early gold coin of the Republic will do as well, a charming 20 As piece with Mars and an Eagle

on Thunderbolt minted about 212BC. Money, gold, and lots of it, financed a lifestyle where this all-black

dining room would demand great amounts of expensive lighting.

- Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

- Sculptures from the Villa of the Papyri - A Philosophers Home

- Vesuvian Villas, Boscoreale, Oplontis, Stabiae and Villa of Mysteries

- Puteoli, Cumae and the ageless Sibyl

- Pompeian Frescos at the Naples Archaeological Museum

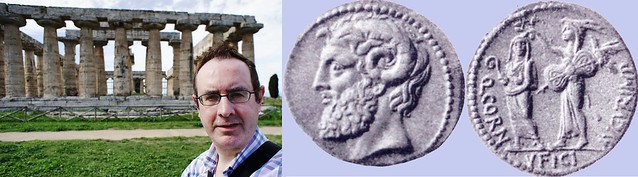

Paestum: a Greek, Lucanian and Roman City

Poseidonia, the Roman Paestum, founded by Greek refugees about 600BC, is famous for its three intact Greek temples of the finest style as well as for tomb art-works of the Lucanians who occupied the city before the Romans arrived in 273BC. That the city has come down to us so intact is for reasons similar to Ephesus: it was abandoned. Whilst the city was running as normal until the early 4th century AD - elections of decurions and so on - shortly afterwards archaeological evidence shows garbage pits being dug in the Forum, and limekilns installed in abandoned private houses. The swamps encroached, water supplies dried up, malaria took its toll and the population died or moved on. The pictures and stories below are thanks to Paestum being left entirely alone for 1500 years.

Click for Slide-Show of Paestum

Click on any picture below to enlarge

Ambrosia, the food, and nectar, the drink of the gods, were made of honey. I sing of honey, the heavenly ethereal gift,

sweet scented, flavoured with thyme, said Virgil. In his Anabasis, Xenophon describes the psychadelic and intoxicating

effects of honey from rhododendron-eating bees.

Honey which the bees collect from the sweet juices of flowers, so beneficial to health says Pliny the Elder in his Natural

History. Cicero in De Senectute describes how wild honey is collected in the forests. A Roman host

welcomed his visitors with the words: Here is honey which God provided for your health. What can we make of this

stunning bronze amphora filled with honey, still good to eat today? In 1952 an underground shrine was found in Paestum

containing not a body but eight large bronze vessels and a Athenian black-figure ceramic amphora, all filled with honey and sealed

with wax, dating from 510BC when Paestum or Poseidonia was a truly Greek city, and thought to be a

heroon or symbolic tomb of the heroic founder of the city. Can you

imagine a more rich and luscious funeral gift than jars of honey - get away you ye gold, silver and riches! There

is no Roman Republican coin with quite as nice an amphora, but Athens, under the sway of Rome from 183BC, and

under an even firmer hand after the sack of Corinth in 146BC, minted this new-style tetradrachm in 142BC showing as all

these coins do a lovely amphora, probably of olive oil, a proud Athenian export product, and perhaps meant as a

prize amphora in the Panathanaic games.

The first Temple of Hera or Juno at Paestum dating from 550BC has an archaic look to it. Unusually two temples

side by side were dedicated to Hera, this Hera I and below Hera II. It has 9 by 18 columns, all intact

making it one of the best preserved archaic Doric temples in the ancient Greek world. Unlike the norm in later temples

there wasn't a frieze with carved metopes - not even a fragment of a metope has been found. The form of the columns

swelling noticeably at their lower end gives the visual impression of them being heavily compressed, bearing

a great weight. The two temples were part of a large sanctuary to Hera that included several minor temples and

altars. Some distance away, past the Forum and Gymnasium, lay the third main temple, that of Athena. Paestum's

focus on Hera was not reflected by Roman dedication to Juno. Juno, sister and wife of Jupiter,

does appear on the coinage from time to time, but most frequently in specialised roles, such as Juno Moneta

- perhaps named for her warning role (monere, to warn) when her sacred Geese alerted the Romans to the Gauls

in 390BC - or as Juno Sospita or saviour, protector of Rome. This rare coin shows Juno Sospita wearing her customary

goat-skin headdress crowning the Augur, Quintus Cornuficius.

The second Temple of Hera has a more classic form, reminscent in shape to that on the Acropolis

but with a 6 x 14 column shape rather than the Parthenon's 8 x 17. One of the best preserved temples in the

ancient world, built around

470BC it is profoundly classical, with a lighter slender look compared with the first temple, although experts

will know that it doesn't have the optical correction or entasis

applied to the columns. Oddly, the pronounced entasis applied to the Temple of Hera I above was certainly not

intended at promoting a slim and light look but probably the reverse, to promote weightiness.

The denarius of Marcus Volteius shows a classically Roman temple, that of Jupiter

Capitolinus, from the same face-on viewpoint. The roof ornaments are unclear, perhaps aplustres, ornamental

wing or branch-like shapes as used for decoration on ships stern.

Search for images of Paestum and you find hundreds

of temples - not just three - but little else. Magnificent as they are, every visitor to Paestum knows there are

many artifacts that are just as interesting though less photogenic. This swimming pool dais is one of the

more intriguing and less obvious. Romans bathed in baths, sea or rivers, but

against tradition Roman Paestum built this large and deep swimming pool in the 2nd century BC. The structure

at the end, inside the pool is uncertain. It could be a judges platform but why place it inside the pool?

Some think there was a more direct function, as an underwater obstacle course. Intriguing. The second building

on the coin is Paestum's two storied city senate or Curia - where the Decurions met -

a rare example on a coin of a non-religious two story

functional building. The coin is small and worn but the building's form is quite clear.

The Tomb of the Diver in Paestum is the only Greek painting to survive in its entirety and the only Greek tomb

painting subject to depict people. The Greek's didn't master

the muse of painting, after having ticked off astronomy, architecture, poetry, philosophy etc.

The evidence sheet remained blank until the 1968

discovery of this one tomb, a mile outside Paestum, with its inner painted slabs dating from the Greek period about 450BC.

The tomb contained just the body of a young man, his drinking flask and his oil jar for use in the gymnasium of the

underworld. The subject matters are remarkable: the upper slab gives the tomb its name. It shows the

dive into the unknown, the journey into the afterlife, with no return. A very simple metaphor. Just before the dive

a flautist leads the young man away from

the party. It was difficult to match this evocative scene with a coin, pictures of youth perhaps,

Apollo, perhaps even breaking my convention

and showing the Villa of the Papyri

sculpture of a youth on a rock, but in the end the Diver's Tomb so wholly reflects Paestum that instead I chose

a typically Paestum coin, a Semis from about 50BC with rudder, anchor and magistrates names.

The banqueting scene in the Tomb of the Diver is almost as popular as that of the Diver. This is a scene of

partying, merrymaking, fun and affection that you might think wouldn't pass a Roman censor. At least if this was on a

Roman Pompeian wall, the three-couched Triclinium with its togate figures would have been replaced by Cupids or

Pygmies of the sort seen in the House of the Vettii. There is lots of sex on Pompeian walls, indeed Naples has

its Secret Cabinet full of priapic figures,

but not much fun or tenderness,

although the Warren Cup

is a glimpse into what might not have been painted on their walls. Much drinking of wine as well as tossing

wine from one's cup into another's, a popular Greek party game, feature in these side-wall frescos. For the young

man now departed this is wistful look back on the pleasures of life. Likely this fresco was only seen for some hours

in its display before the tomb was sealed; those Paestum citizens who did see these scenes would come away with

the message, have fun, enjoy life's pleasures now. For a matching Roman numismatic context, only the

ever happy figure of Bacchus will do, on this attractive coin of Marcus Volteius from 78BC. It's reverse shows

Ceres, bringer of the corn supply to Rome

in a biga drawn by snakes, symbols of health and welfare, thus bringing together wine and food, health and welfare.

But perhaps not quite fun and affection.

Lucanians were a warlike indigenous Italian tribe living in the mountainous area south of Campania but

north of Italy's Calabrian toe. They waged war at the edges of their region through much of the first millenium BC.

The Greek city Paestum at the southern limits of Campania was a tasty target and they moved in about 400BC.

Somehow the Greek culture seems to have survived, and finds of fine pottery date throught the Lucanian period

until the arrival

of the Romans in 273BC. Indeed when Alexander of Epirus fought against the Lucanians and

Samnites in treaty with the Romans in 332BC, he was allied with the peoples of Paestum and other cities of

Magna Graecia. Yet Paestum is now famous for its Lucanian era painted tombs, such as that with the fighting

warriors pictured here, or another with

Victory with a two-horse chariot or biga. Perhaps the war-like Lucanians subsumed themselves into the city's

Greek cultural practices, adding the Lucanian flavour to the painted tombs. It would not be the first time that

an invading force merged with the better aspects of local cultures. Still, the Lucanian tombs are remarkably

different from Greek figuration - and remarkably war-like. This particular one looks likes a child's view

of warfare, heroically undressed and muscular youths with wounds no more serious than bleeding thighs, a

Boys Own Paper version of warfare.

Lucanian armour and many other

Lucanian era artifacts at Paestum are near indistinguishable from those of the Samnites.

Perhaps the geographic distinction between the various Italic mountainous warrior tribes is artificial.

The coin of Quintus Thermus Minucius shows a similarly boyish view of fighting soldiers which doesn't quite

tally with what we read about Roman military technique. Recruits were taught not to chop but to thrust with their

swords and the Romans made fun of enemies who chopped, finding them an easy conquest.

This red-figured amphora from Paestum is beautiful and elegant, in form much as the jug on the coin of Aulus Hirtius

minted for Julius Caesar's quadruple triumph in 46BC.

Amphorae of similar quality can be seen in the Paestum museum, and some are identified

as marriage gifts, indeed possibly this is such a gift. Whilst it dates from the Lucanian - Samnite era in Paestum

4th century BC, it is entirely Greek in quality and form. It is touching to think back to a real woman who would

have received this gift. Perhaps she adored it, perhaps she'd have rathered sheets, tableware and a toaster.

Ancient Greek

marriage happened by ritual rather than by civic or religious control. It started with cleansing at baths, then the

groom visited the bride's father's house for a feast, then took his bride to his parent's house where they

would be greeted, brought to the hearth and showered with nuts and fruit before retiring.

A child had to be conceived from their union for the wife to be

accepted fully into the groom's family.

- Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

- Paestum, a Greek, Samnite and Roman City

- Vesuvian Villas, Boscoreale, Oplontis, Stabiae and Villa of Mysteries

- Puteoli, Cumae and the ageless Sibyl

- Pompeian Frescos at the Naples Archaeological Museum

Sculptures from the Villa of the Papyri - A Philosophers Home

The Villa of the Papyri, was named after its large library of philosophical books but is better known for its sculptures, among the greatest treasures from the ancient world, a match perhaps for Tutankhamen's tomb, and all from a private house in Herculaneum. It was excavated between 1750 and 1765 by Karl Weber by underground tunnels, and the statues all now reside in the Naples Archaeological Museum. Most relate to philosophical subjects - as do the library books - but a few exceptional pieces, for example the athletes, seem chosen just for their hedonistic beauty. The house was owned by Caesar's father in law Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Consul 58BC, and his descendents. There's an excellent website, AD79 Destruction and Rediscovery that gives a good overview of the Villa of the Papyri and other Vesuvian villas including a poolside photograph taken shortly before the eruption. Nice!

Click for Slide-Show of Villa of Papyri Sculptures

Click on any picture below to enlarge

This portrait bust of Pyrhhus of Epirus, known today for his so-called Pyrrhic victories at Heraclea 280BC and Asculum 279BC

over the Consuls Publius Decimus Mus and Publius Valerius Laevinus, but with losses he could not sustain in the longer term

is shown with a Campania minted didrachm likely used to fund the war for Rome. Pyrrhus also wrote Memoirs and books

on the art of war, now since lost, although, according to Plutarch, they influenced Hannibal and

Cicero praised them.

The athletes of the Villa Papyri are its best known sculptures. Lucius Plaetorius issued an athelete-themed

set of coins in 71BC, each showing a different athletic object in addition to the runner with palm leaf and cestus,

which is a sort of knuckle-duster or metal gauntlet. On this coin, an oil jar is shown below.

Other coins in the series show a discus, strigil and other stuff useful in a gymnasium.

Organized athletic competitions had their origins in ancient Greek funerals, specially of warriors

who were honoured with activities taken from the lives they had just left,

and often involving skills necessary in war. The Romans were less concerned with athletics as spectator performance art,

instead seeing athletics as a useful tool for promoting physical fitness in the gymnasium.

Despite many good things about Roman culture such as their respect for the life of the citizen, their

forms of democracy and justice, and their social provisions for the urban poor and retired soldiers,

they went off on an immoral and misguided tangent in choosing bloody gladiatorial games over healthy athletics for

entertainment.

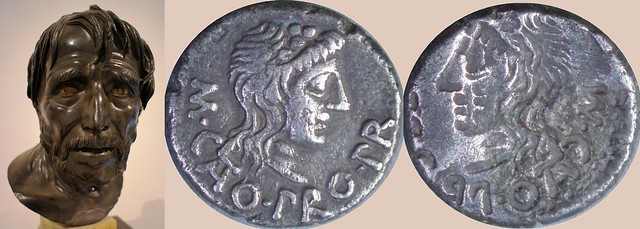

The statue of Hermes or the Roman Mercury is more of artistic beauty than philosophical interest. Mercury appears on

many Roman coins but this of the Italian city Luceria from the second Punic war is amongst the better

artistic representations on a struck bronze. Hermes or Mercury had a wide range of gnerally benign responsibilities

including animal husbandry, roads, travel, hospitality, heraldry, messaging, diplomacy, trade, language, writing,

persuasion, trickery (hmmm less benign), athletic contests, gymnasiums, astronomy, and astrology. It's his role as

messenger that is best known, for which he wore winged boots and a winged travellers cap, and carried a

caduceus, a staff with intertwined serpents, sometimes winged, and all nicely

shown on this little bronze of

Venusia. I know of no other coin

with such a nice boot.

Scipio Aemilianus, besides a soldier and statesman, was a man of the arts. He was a friend of the Greek historian Polybius,

the philosopher Panaetius, and poets Lucilius and Terence. His year of destiny was 147-146BC when as Consul he

utterly defeated Carthage, in the same year that Corinth was razed. This denarius of his consulship is of the traditional

early Dioscuri design, soon to be superseded.

Lucius Calpurnius Piso Pontifex, owner of the villa and brother-in-law of Julius Caesar - Caesar's wife was Calpurnia -

left an elegant portrait bust which somehow bears similarities to Julius Caesar though not of blood family. The Calpurnia

gens had an history of pontifical appointments. This coin of 58BC likely of an uncle, Marcus Piso Frugi, shows the

pontifical implements: patera, knife and dish. The word pontifex literally means bridge-maker and their role

was to maintain peace with the gods, by ensuring religious procedures and ceremonies were properly followed. In

contrast with many other religions, being a pontifex was no bar to political office or military leadership.

Indeed it was a useful source of secondary power - the ability to commune with the gods - and much sought

after by leading men of the Roman Republic.

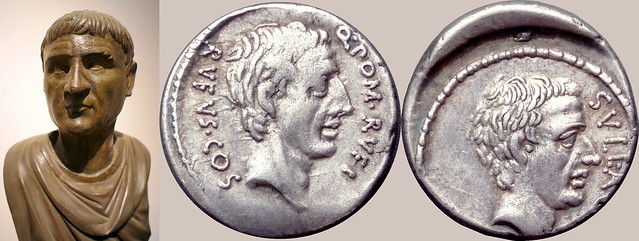

Sulla, with his characteristically curly hair, was less a philosopher and more of a luvvy. Until old age, and most

specially in retirement, he kept company with actresses, musicians, and dancers, night and day. Perhap's the villa's

philosophical owners commemorated rather his commentaries or memoirs, which survive today only through fragments quoted

by others. Sulla's son, Publius Cornelius, issued this portrait coin together with Quintus Pompeius Rufus in 54BC.

Uncyclopaedia's article on Sulla

presents an oddly believable version of his life, with his company of bad actors, dirty dancers, and terrible singers, his

penchant for dim and ill repute tavernas but nevertheless getting just about the right tone on his

long feud with Super Marius.

This bust is reputed to show Seneca, Stoic philosopher and statesman, Nero's prime minister in effect. The most well-known

Stoic philosopher and statesman in the Roman Republican was Marcus Porcia Cato Uticensis. This quinarius of his, of African mintage, is a

brockage nicely showing his name and titles on both sides. The word Stoic comes from the porch or "stoa poikile"

in the Athenian Agora where discussions took place amongst a group of new philosophers who considered that

emotions such as fear, envy or love arose from false judgements and that a sage could forego them through will.

Such harmless ideas when applied to one's personal life proved dangerously rigid in the politics of Cato,

one of the least flexible, hardest and most unaccommodating politicians of Roman times. If politics is the art of

compromise, with the aim of generating the most happiness for the most people, Cato's utter dismissal of

compromise as a technique, and of welfare and happiness as aims, was bound to end in tears.

Marble rather than bronze cloaks this statue of Nike with a marvellous shoulder aegis - the scaly skin of a guardian

snake with a Medusa head at centre - whose pattern is repeated in a denarius of Manius Cordius Rufus in 46BC.

When you Google "aegis", the first picture in the first reference is of the aegis on this statue so it is as representative

as it comes.

- Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

- Paestum, a Greek, Samnite and Roman City

- Sculptures from the Villa of the Papyri - A Philosophers Home

- Puteoli, Cumae and the ageless Sibyl

- Pompeian Frescos at the Naples Archaeological Museum

Vesuvian Villas: Boscoreale, Oplontis, Stabiae and Villa of Mysteries

Everyone who visits Naples visits Pompeii, and that is probably a mistake. After five hours tramping up and down streets through forums, amphitheatres and temples, passing shuttered doors of houses under renovation and looking into dusty remains of shops, there's less appetite for seeing more Vesuviana. The next stop is usually the Naples Archaeological Museum where one thinks "This is what used to be in Pompeii. Very nice. Let's get a pizza". But many of the most stimulating Vesuvian remains lie inside countryside villas, and there are few of these actually in Pompeii. So lets look around some of the best villas which are in the vicinity of, but not at Pompeii or Herculaneum: Villa Poppaea at Oplontis; the Villas at Stabiae; a set of fine houses called San Marco, Shepherd, Arianna, Anteros and Hercules, Carmiano, and Petraro, grouped in one complex; Boscoreale Villa Regina; the Villa of Mysteries; and Boscoreale Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor. These - except the Villa of Mysteries which can be walked from Pompeii - are really difficult to get to, unless you are fit and used to taking a bus and walking, and have time on your hands. But if you team up with friends and family then a hired driver can take you around almost as economically as a guided coach tour. NB I only saw the Villa Synistor in its NY and Naples museum incarnations. Other Villa's of note are Boscoreale's Villa Pisanella and Villa of Agrippa Postumus, recovered by fresh lava in 1909, so bring a spade. Further from the main centres in separate locations are the Villa of Augustus near Vesuvius summit, Tergizio Villas, Villa Sora at Torre del Greco, and the Inn of the Sulpicii in Murecine. There are also several villas at the edges of Pompeii, probably not worthing visiting given their ruinous condition and better treats inside the walls, but for historical completeness it does include Cicero's house although he was not at home during the volcanic eruption, having had his head lopped off in 43BC. The grandeur of Pompeii will await another day and another trip to Naples. The House of the Vettii in Pompeii would be the star of any visit to Naples but has been closed for ages for renovations - perhaps they are repainting the walls - which gives me a great incentive to visit again.

Click for Slide-Show of Vesuvian Villas

Click on any picture below to enlarge

This red room is from a Stabiae Villa. Pompeian red evokes Cinnabar of pure Vermilion colour,

a natural sulphate of mercury HgS, prized by the Roman's for its

vibrant and deep red. Vermilion abounds on the walls of the Villa of Mysteries,

making the enigmatic pictorial cycle one of the most intense of the ancient world. It seems to have been pricey

relative to other colours but not greatly so - Mary Beard cites a price-control limiting Cinnabar to twice that

of other colours. However many Pompeian

colours darkened due to the effects of volcanic heat, and Crimson may be a better guess as to what

this Stabiae room once looked like. Crimson is a dusky colour between red and rose.

Red Ochre based on ferrous oxides and haemetite was plentifully available and cheap, Italy being

awash with ferruginous copper as its early currency bars attest such as the one pictured.

Red Ochre was known as Rubrica Sinopica being an important product of Sinope, but no doubt there were

local recipies. When mixed with Sandaracha, the pale yellow oxide of lead, it makes Crimson. Pompeii's colour

may have been as much a product of local red-yellow iron and lead oxides, as of deep-red mercury.

The Boscoreale Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor is awash with architectural wall painting. Some important frescos

are in New York's Metropolitai, but this one is from Naples. It's easy to gaze at the general colours and

architectural form, wallow in red so to speak, but it pays dividends to look at the details (click the picture for larger view).

There are theatre masks above, that on right could be Pan - a satyr with a man's upper body and goat legs - or

Silenus, a human of similar looks and companion to Dionysus. The coin of Silanus shows a punning Silenus mask, note

the lack of neck and open mouth showing this is a theatre prop and not a bust. Theatrical motifs abound in the

Vesuvian cities and villas, though it is difficult to know if this was merely decorative. We do know that

whilst detailed programmes of gladiatorial shows abound at Pompeii, playbills don't. Perhaps it was something

for private houses rather than public theatre.

Dionysus the ancient Greek god of the grape harvest, winemaking and wine, of ritual madness and ecstasy, was the

Roman Bacchus that features elsewhere on this web-page. The intoxicated wildness of the Bacchanalia comes

to mind when the Roman god's name is mentioned. Dionysus, the same god, suggests the Villa of the Mysteries

and its vermilion red paintings, supposedly representing the initiation of a woman into the Dionysian or

Bacchanalian rituals. On the outskirts of Pompeii beyond the Herculaneum gate this villa is overlooked by many

visitors and has a quiet and serene atmosphere. Most surprising is that unlike many other houses the best frescos

have not been moved to Naples but are intact. You can find some time all alone to contemplate these

great paintings, still on the walls where the frescos were created. Rather than another coin of Roman Bacchus, the

Greek Dionysus is shown on this coin of Gaius Papirius Carbo, Proconsul in Bithynia 59BC. Coins of the

1st century BC Asian magistrates are among the most interesting in the Roman Republican series because unlike

the coins of Rome that display a junior mint magistrate with perhaps family links to those in power, here you get

men of history with their own names on the coins just as with the later imperators but with the mandate of the

Senate and People of Rome.

Primavera of Stabiae, the Spring of Stabiae, is one of the most refined and gentle paintings of the Vesuvian villas

depicting a lady in a yellow dress casually picking flowers against a green background. Whilst the best known of the

Stabiae frescos it's surprisingly small, a foot-square painting. She has her equally elegant sister beside her,

Diana with bow and arrow against a blue background. These are a good match of the Greek Muses, on the coins of

Quintus Pomponius Musa. Statues of the nine muses along with their leader Hercules Musagetes were brought from

Ambracia in Greece by Marcus Fulvius Nobilor, Consul 189BC, who established the temple of Hercules and the Muses

in the Circus Flaminius. Erato, the muse of erotic poetry, has a flower behind her head and on its reverse she is

shown with a many stringed lyre, distinguishing this type from the otherwise similar Terpsichore.

In 135BC, Cauis Minucius Augurinus issued a remarkable coin, perhaps only the third denarius having a

non-standard Biga or Dioscuri design, after the coins of Veturia and Pompeia in 137BC. It shows a column with

bells and trinkets, flourishes, corn-ears and striations, a statue on top and ancestors surrounding. What and

where in Rome this column was has confounded numismatists for centuries but it likely honours Lucius Minucius,

prefect of corn supply in 439BC, and Minucius Festus, one of the first plebians elected as augur in 300BC

hence the family cognomen. In the 2009 International Numismatic Congress a paper suggested that the column

was a merely comemmorative fantasy and never existed in stone or marble.

This makes more sense when you see the delicate wall frescos of Stabiae. For what else can these be but

fantasy columns, intricate light playful and decorative with ornamental figurines. Lovely.

Oplontis was a town near Pompeii, with a large villa discovered in the late Rennaissance, 1590,

but only partially excavated in the 19th century, and mostly uncovered in the 1960s-1980s although about a third

remains unexcavated under modern buildings in Torre d'Annunziata. It was buried under the protective pyroclastic

surge as with Herculaneum, a muddy dilute mix of hot gas, water and lava fragments,

rather than by the pumice showers of Pompeii. Visually the largest and most spectacular uncovered villa in

Vesuviana - the Villa of the Papyri being mostly covered. Excavators sought out a palatial

homeowner to name the house after, and settled on Nero's wife Poppaea, although when one thinks a

little deeper it's perhaps not surprising to find souvenirs of a ruling family in any of the more palatial

Pompeian villas just as any English country house today is littered with royal commemorative tat. Nero was

of course a Julio-Claudian emperor, but by birth was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. His link to the Julio-Claudians

came from both sides. His mother Agrippina Junior's parentage goes back to Agrippa on her father's side and

Mark Antony

on her mother's side. Mark Antony's wife Octavia was Octavian's sister and the great-niece of Julius Caesar.

Nero's father Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus was the grand-nephew of Octavian again through the Antonia - Mark Antony line.

So Nero's link to Julius Caesar and his line is exceptionally tenuous whereas he was the great-grandson of

Ahenobarbus the Imperator. This coin of Ahenobarbus is as much an Imperial family portrait as of an Imperator.

Perhaps the family should have been called Julio-Claudio-Domitians. Poppaea Sabina does seem to have come from

the Pompeii area and, as her family name shows, was decidely not of old Roman blood but Sabine.

The vineyard farmstead, Villa Regine at Boscoreale, is often confused with the frescoed Villa of

Publius Fannius Synistor in Boscoreale but is a more modest dwelling and more interesting in ways. In its yard are

dolia or winejars of 10,000 litres.

This gives scale to the villa, which probably had some 3 acres of vineyards.

In Republican times wine retailed at about a sestertius a litre.

Allowing for some retailing costs this farmstead may have netted about 2000 denarii or in today's terms

about £20,000 per year. This was about 10 times the pay of a legionary or semiskilled worker who would happily

survive and feed a small family on 200 denarii a year, in today's terms about £2,000, well above a subsistance

level but hardly allowing for much in the way of luxuries.

The Vineyard owner was richer and happily middle-class by Roman standards,

enough to afford a couple of high quality artworks as shown below, probably owned a couple of slaves each of whom would have cost

much of a years income, 500 to 1000 denarii or so depending on strength and good looks. Still, add up the sums of

cost of living in Roman times, together with running and investing in the farmstead,

and the lifestyle was modest and the work hard. It hardly compares to the Villa of the Papyri. The coin, dating

from 170BC has a butterfly sitting on a vine leaf with heavily loaded bunches of grapes. I wonder was the mint

magistrate for that year an oenophile.

The Farnese sculptures in the Naples Archaeological Museum are impressive. Even on a first visit

there's a suggestion you've seen them all before, so familiar are their images. None come larger than the

Farnese Bull found in 1546 in the baths

of Caracalla. Dirce was tied to the horns of a wild bull by Amphion and Zethus as punishment for her mistreatment

of their their mother Antiope, Dirce's niece. The Farnese Bull is gross, too big and coarse in subject.

This charming domestic sculpture of a dog killing a rabbit found in the Villa Regina is quite the opposite,

domestic, natural, sympathetic even in its violence and a fine art-work suited for any middle-class home. This

tiny one-sixteenth ounce bronze with a dog dating from the 230s BC is similarly charming.

Bacchus appears throughout this web-page but I couldn't omit this sculpture from the vineyard house of

Villa Regina. This was no doubt the proudest posession of the middling prosperous vineyard owner, a sculpture

themed with his profession. Perhaps he'd comissioned it or maybe visiting artisans toured the villas of

Campania with pattern-books of sculptures appropriate to any lifestyle. It's a fine style terminal bust

though not in the artistic league of the Villa of the Papyri sculptures. The coin of Lucius Cassius, 78BC,

has the best portrait of Bacchus on a Roman coin, ivy leaves and berries in his hair and a thyrsus by his

shoulder, a staff of fennel wood with ivy leaves. The other child of Ceres, Libera, is on the obverse

wearing vine leaves in her hair. No doubt this commemorates Spurius Cassius Vecellinus,

Consul in 502BC, 493BC and 468BC. He dedicated a temple to Ceres and her children Bacchus and Libera

during the Latin war of 498BC. His thirty-four year gap in consulships is as long a period as I know.

- Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

- Paestum, a Greek, Samnite and Roman City

- Sculptures from the Villa of the Papyri - A Philosophers Home

- Vesuvian Villas, Boscoreale, Oplontis, Stabiae and Villa of Mysteries

- Pompeian Frescos at the Naples Archaeological Museum

Puteoli, Cumae and the ageless Sibyl

The northern shore of the bay of Naples was unaffected by the Vesuvius but it was also where the prime villas of the Roman wealthy lay, so earthquake or not there are archaeological remains all over the place. The most fmaous Roman towns were Puteoli - modern Pozzuoli - Cumae, Baiae and the naval base Misenum from where Pliny the Elder set off on his rescue mission on the day of the volcano, to his untimely death on a beach near Pompeii. Pliny the Younger later described the circumstances in detail in a letter to Tacitus. Puteoli as the wealthiest coastal resort town, and Cumae with its ancient Greek hilltop temples probably have the best remains. Much of Baiae is now underwater due to frequent changes in ground levels, both up and down, over the centuries caused by underground flows of volcanic material. Looking across the Bay of Naples from Pozzuoli today you will see much the same view as the Romans would have two thousand years ago.

Click for Slide-Show of Puteoli and Cumae

Click on any picture below to enlarge

The Sibyl of Cumae as a young and beautiful woman attracted the attention of Apollo who offered her anything if she

would spend a single night with him. She asked for as many years of life as grains of sand she could hold in her hand.

Apollo granted the wish but she then refused his advances and was cursed to get the asked-for long life but without

eternal youth, shrivelling into an old crone. She lived out her long life from the very cave shown here,

writing prophecies on leaves placed at the entrance, to be picked up and read or scattered to the winds.

In the time of King Tarquin Superbus she

entered Roman Republican lore when she offered 12 books of prophecies to the king, burning volumes until he agreed

to pay for the last three at the same price for which she'd offered 12. Thereafter they were kept in the Capitol and consulted at critical

times by the Senate. Some were destroyed by fire in 83BC while the rest survived until late Empire. Whilst the

original Sibyl vanished when sought by King Tarquin, through Roman times a visitor to Cumae would, for a price,

be able the consult the Sibyl, a priestess of Apollo at Cumae, likely out of these caves and possibly through the

means of prophecies written on leaves. The cave was discovered at Cumae in 1932 and identified as the site of the

prophetess Sibyl by its description in Virgil. This may or may not be true but the Sibylline books certainly did

exist and were consulted by the Senate at Rome. Believe what you will. This coin of Torquatus 58BC shows a

Tripod and the ageless Sibyl with her name written below her head.

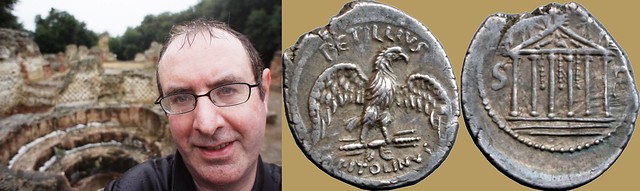

The Sibyl showed herself to me in a strange and fearful atmosphere on a wet day in October 2010. There was a fierce

and drenching storm and when I arrived at the gate of Cumae I was soaked through. Going forward

rather than back made sense though not to the guardians of the archaeological park who shook their heads in

concern as I wended along the inclined road towards - towards I didn't know what, with no map or guide book

of Cumae - towards a very large dark tunnel where waiting for me was the

Sybilline hound and its puppy, who

gave clear "follow me" signals, through the tunnel, on the other side a desolate wooded hillside with unmarked

paths. Without another marker, I followed the dog, who

clambered a cliff ledge, barked to the skies

and leaped down and ran towards the cliff-face. It to my rain-drenched brain that the the dog was leading me to the Sibyl

as she howled into the trapezoidal cave entrance. There was thunder and rain and no-one else around.

The dog bounded into the cave,

checking I would follow one last time,

leading me into a mystical passage just as seen by

Aeneas when he consulted the Cumaean Sibyl,

who conducted him through the Underworld and revealed his destiny to him. Finally I was at the heart

of the cave, as in the photo above, but the hound had vanished and I was alone. Had I met the Sibyl?

Only later I regretted after that I failed to catch the leaves with the Sibyl's own prophecy for me. October 2010,

in the pre-packed modern tourist destination of Naples, such things can happen.

This very rare coin of Valerius Acisculus shows a young Sibyl opposite her youthful would-be lover Apollo.

There's two large temple complexes at Cumae - that of Apollo and Jupiter - with a

winding processional rainy road between.

The Cumae archaeological park spreads over a wide area and I explored it alone and without directions,

stumbling on finds. The

Temple of Jupiter

is at the summit of Cumae hill, and the drawings at site helped me interpret it but I'd have been content

to wander unguided so long as I could find it. It's most dramatic feature is the circular well in photo. I'd

almost rather not have known that this may have been a Christian era addition and just let my imagination roam.

The remains are still more impressive than those of Jupiter Capitolinus at Rome of which foundations only remain.

The best ancient remnants of that temple are actually on this coin of Petillius Capitolinus. The keeper of the Temple of Jupiter

at Rome was hereditary in the Petillius family, and from this they took their name — the respected Capitolinus.

In 181BC in the lands of Lucius Petillius, at the foot of the Janiculum hill,

the sacred books of King Numa were found in stone chests with lead joinings, some 500 years after his reign. Or

perhaps not, rather depending on the reliablility of Lucius Petillius' testimony.

Pozzuoli or Roman Puteoli has a terrific amphitheatre, the third largest after the Colosseum and Capuan arenas.

It's difficult to get good photographs of an amphitheatre unless from an airplane; some flat ground and plain

rows of stone seats is the usual result. I did take a

270 degree fish-eye view of the arena

but it's more flat ground and more rows of stone seats. However the underground chambers at Puteoli are the best

I've ever seen, much nicer than the Colosseum, well preserved and with plenty of room for gladiators, beasts, arms,

and mobile equipment. You can imagine how busy it would have been. I'm not clear why the opening needed to cut

across the centre of the arena or even why it had to be underground, but stage-management obviously required

men, beasts or equipment to arise from below. The coin of Titus Didius of 113BC shows a classic gladiatorial scene

in that the two combatants have differing weapons.

Lacking an aerial view of Puteoli, this marvellous and ancient aerial view of the Pompeii arena shows what the

Romans thought their amphitheatres looked like. But what's going on? There's fighting all over the place and not

just in the arena! This is a painting of the famed amphitheatre riot of 59AD, and the account of Tacitus:

"About this time [AD 59] there was a serious fight between the inhabitants of two Roman settlements,

Nuceria and Pompeii. It arose out of a trifling incident at a gladiatorial show. During an exchange of taunts,

characteristic of these disorderly country towns, abuse led to stone-throwing, and then swords were drawn.

The people of Pompeii, where the show was held, came off best. Many wounded and mutilated Nucerians

were taken to the capital. Many bereavements, too, were suffered by parents and children.

The emperor instructed the senate to investigate the affair. The senate passed it to the consuls.

When they reported back, the senate debarred Pompeii from holding any similar gathering for ten years.

Illegal associations in the town were dissolved, and the sponsor of the show and his fellow-instigators

of the disorder were exiled". Mary Beard looked further into the details and consequences. It seems that the

Duoviri were amongst those exiled in 59AD as there are two sets of Duoviri named for 59AD. And games did

continue over the following decade, but without gladiators. It's a rather interesting example of

Imperial intervention in local politics. The gladiatorial scene from Livineius Regulus' coin is a classic

display of men and beasts - two gladiators, a lion, panther and boar - but doesn't quite capture the

riotous football-crowd scenes of this story.

Conservation and archaeological funding is in short supply in Italy relative to the sheer wealth of opportunities

to investigate, conserve and display. There's just too much nice stuff. The Puteoli amphitheatre was once

decorated with marble facings and statues, and whilst that marbling is gone from the arena, there are

unbelievable volumes of discarded marble fragments

just lying about and protected by no more than a 6 foot fence. These Ionic capitals appealed to me so nicely carved

but I couldn't photograph them without including the pig behind whose rear end you can clearly see. I can't

imagine what statue arrangement would have called on a pig but perhaps there was a sacrifice scene. Pigs feature

prominently on coins of the Roman Republic, in sacrifices or in attendance on other scenes, and sometimes just on

their own as in this attractive Victoriatus. The Romans liked their pork.

This is another terrific piece of discarded masonry at Puteoli and it's difficult to imagine where it would

have been located. It is too detailed and not the right shape for a capital but one could imagine it at the edge

of the platform or dais where the Decurions sat. Look closely - click on the photo to enlarge -

and you'll see marvellously sculpted armour laid out in an attractive, artistic and lifelike manner.

Those chest plates look more human than marble. The coin of Mark Antony from 37BC has much the same elements

in its trophy as the Puteoli sculptures but the life-like marble wins hands-down.

- Herculaneum: Roman Domestic Life

- Paestum, a Greek, Samnite and Roman City

- Sculptures from the Villa of the Papyri - A Philosophers Home

- Vesuvian Villas, Boscoreale, Oplontis, Stabiae and Villa of Mysteries

- Puteoli, Cumae and the ageless Sibyl

Pompeian Frescos at the Naples Archaeological Museum

Many of the best frescos now at Naples were excavated from Pompeii or Herculaneum in the Bourbon digs from 1738 onwards, by Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre and Karl Jakob Weber. Excavations were initially by tunneling and thus broke through walls, frescos and mosaics at unplanned points. Traces of early excavations can still be seen in places. The Bourbons focussed on the quick recovery of sculptures and fresco paintings, rather than on systematic archaeology in todays manner. The best evidence for Pompeian painting techniques comes from the House of the Painters at Work where painters' pots and brushes were found in a room where several panels bear only the sketched outlines of the proposed decoration to be worked up later. There was evidence of wet fresco technique and a pot of wet plaster on a scaffold that fell against the wall when the roof caved in. They were working on the very day of the eruption, but there was ongoing repair or decorative work in many other Pompeian houses too. This can't be due to the 62AD earthquake - why wait 17 years for last minute repairs? More likely according to Mary Beard there had been ongoing earth tremors and damage in the weeks and months leading up to the eruption, that needed some plaster and a lick of paint. As for the four styles of Pompeian painting, well don't worry if you can't tell them apart. Many frescos don't fit neatly into one or other style and the styles did not all follow neatly in sequence.

Click for Slide-Show of Pompeian Frescos

Click on any picture below to enlarge

Sacrifice scenes abound on Roman Republican coins. I chose this one from a coin of Aulus Postumius 81BC because

of its clear layout with priest, altar, bull. Other nice examples include a

goat sacrifice on a coin of

Pomponius Molo and a

cute pig in a Social War sacrifice.

Even when the full picture isn't shown, anywhere there are knives, pateras and bowls on Republican coins

you can bet a squealing sow was not far away. The Pompeian picture is not actually of a sacrifice scene despite

the bull and altar-like table, but of the homecoming of Jason - right - welcomed by Pelias - left with the bull -

who was attending a festival and likely bringing the bull to sacrifice.

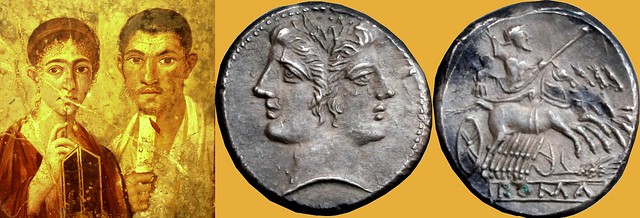

This family portrait of the bread baker Terentius Neo and his wife, found in their home and bakery, is a sensitive study

shaded as if in natural light to bring reality to clothing and form. This is no Apollo, indeed Neo's features

are suggestive of Samnite origins, bbony with a large forehead, and a slightly unkempt beard and moustache.

He looks nervously at the artist, somehow his wife is more poised and elegant, perhaps of a different class.

Significantly she opens her writing tablet to show him, having no secrets. Whilst found in a bakery there is

a view that Neo may have been a lawyer hence the scroll, or perhaps that was a standard prop of literacy? Wheat was

fundamental to Rome, more so than today when potatos and rice play a bigger role. Meals were centered around

grain in one or other form: husked wheat (far) made into porridge (puls), or naked wheat (frumentum) made into bread.

Pompeii was full of bakeries and bread was the staple food in the Roman city, perhaps eaten with oil, fruits or nuts

and herbs to provide a balanced diet, if lucky sweetened with honey or cheese, or eaten with sausage, domestic fowl,

wild game, eggs, or fish. Wheat supply was a key policy objective of the state, Egypt being its breadbasket in

Imperial times and Sicily during the later Republic. For a long period the coins of Sicily were marked with an

ear of wheat, or corn-ear as it usually referenced. This Sicilian didrachm of about 215BC is significant in being the

first ever coin so marked, just before the transition to the new denarius coinage.

About 600BC on the isle of Lesbos in the north east Aegean the female poet Sappho wrote love poems addressed to women

of which only fragments now remain. Half a millenium later a workman painted a fresco of

Perseus and Andromeda on a Pompeian domestic wall, which he framed either side with fine medallion portraits of a man

with a scroll and a woman with tablet and stylus. In May 1760 these were excavated at Pompeii.

The girl wears a golden hairnet and holds a stylus and wax tablet. In time she became known as a portrait of

Sappho with no particularly good reason. Many such portraits bear similar marks of learning, as with the

baker's wife directly above. Better instead to call her Clio, the muse of history, shown on a coin of

Pomponius Musa with a scroll in hand and a further scroll behind the androgynous obverse head. The coins of

Pomponius Musa are not only peculiarly expressive of female talents, but of talents in general aside from the

dark art of war seen on most Roman coinages.

Cupid and Bacchus are everywhere in Pomepeian painting. If Mars tried to find his way into Pompeii

he'd be blocked by hoards of loving drunkards. That's somehow pleasing. Love and wine. The

House of the Vettii

is Cupid Central and this painting in the Naples museum is representative, Cupid with a biga of Swans. The

most Cupidic coin in the Roman Republic has to be this denarius of Lucius Julius Caesar 103BC where

Venus, the goddess of love, beauty and fertility, is driving a biga of Cupids, with a lyre added just in case

you thought there wasn't quite enough fun.

Oddly Mars is on the obverse, a crazy mix of messages. There is another curious coin of Cupid, a quinarius with

Cupid breaking a thunderbolt

on his knee. The thunderbolt on coins is

Roman power in symbol. Perhaps a broken thunderbolt wasn't a favourable omen - there's but a unique example in

Paris of that quinarius.

Images of ships inside arches occur more than once on Roman coins. Archaeological remains in various harbours

suggest ships were generally drawn up inside arched enclosures rather sitting at anchor in water.

A video reconstruction of Carthage harbour shows the

circular harbour, still visible today: ships stayed under cover from the elements, parking under the arches

much as aircraft entering their hangers. So this picture from Pompeii and

coin from Censorninus showing the same image - the ship's prow is under the right hand arch - is how things were

and not the imposition of an arch and a ship from different places. In the remains of

Herculaneum's harbour visible today

there are arched enclosures at the lower levels. Those below the terrace of M. Nonius Balbus are the boathouses

that once lined Herculaneum's ancient shore.

Larinum struck this nice quadrans with centaur sometime in the 2nd century BC. Although Roman in denomination and

marking, it's unlike the solidly Roman format of other towns such as Paestum, Brundisium, Vibo Valentia, Copia or even

Panormus. Symbols of Roman gods such as Thunderbolts,

and symbols of Roman plenty such as Corncucopiae were the marks of choice on civic coins throughout Italy. Prows

rudders and anchors, wolves and twins, eagles, corn-ears, Neptune's trident, Minerva's owl.

All these conveyed the same message of Roman power and wealth.

The coins of little Larinum are pleasantly different, with Greek mythology and no hint of empire. In this way

it reflects what we see at Pompeii and Herculaneum where there's lots of Bacchus, many Satyrs, few thunderbolts and

fewer Martian gods of war. Images of violence were reserved for the gladiatorial arenas, but at home, mythology

was rather more pleasant. This beautiful painting of the centaur, Nessus, with Hercules and Deianira could as well

be a Renaissance work. In Ovid's Metamorphoses story Hercules shot Nessus with an arrow in rescuing Deianira from

the centaur Nessus, who had tried to abduct her in a river crossing. As he lay dying, Nessus tricked Deianira,

telling her that a mixture of olive oil with his semen that he had dropped on the ground and his heart's blood

would ensure that Heracles would never again be unfaithful. Deianira later smeared some of this potion on Heracles'

lionskin shirt, which burned Hercules terribly who threw himself on a funeral pyre. In Greek, Deianira means

man-destroyer. I doubt any but the most misandrous mother would give a daughter that name today.

The ancients had a complex relation to snakes. They were seen as dangerous in mythology. The infant

Hercules strangled snakes

sent by Hera (Juno) when she discovered he was fathered by Zeus with a mortal woman. But they are more often seen in a positive light.

The snake-entwined caducues is the staff of Mercury or Hermes whose origin is unclear. The annual sloughing of a

snakes skin was seen as a symbol of renewal. The cista mystica, a sacred chest or basket, housed snakes

used in the initiation ceremony of the cult of Bacchus, or Dionysus and is usually shown on cistophoric tetradrachms.

Snakes are often shown in altar scenes specially on Roman provincial coins.

This cistophorus of Metellus Scipio has a curious reworking of traditional motifs with the basket on the reverse

and the snakes entwined around a legionary eagle on the obverse. There is nothing more sacred to a Roman general

than his legionary eagles so, oddly, those snakes must have been regarded as an enhancement. Hygieia, or

Roman Salus or Valetudo,

daughter of Asclepius, was goddess of health, cleanliness and sanitation, and had a snake as companion

likely as a regenerative or cleaning motif, odd though that seems to us.

The fresco likewise features snakes in a sense unclear to any modern eye.

It shows a sacrifice scene with pig, altar, all the usual suspects. Below another altar, in foliage and with snakes.

Regeneration.

All content copyright © 2004-2011 Andrew McCabe unless otherwise noted. If you've any questions or comments please contact me on the Yahoo Group RROME: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/RROME.

Alternately you can leave comments against any coin picture, just click on the picture and write in the comment box.

See my rarity estimates for Roman Republican Bronzes: Roman Republic Bronze Rarities..